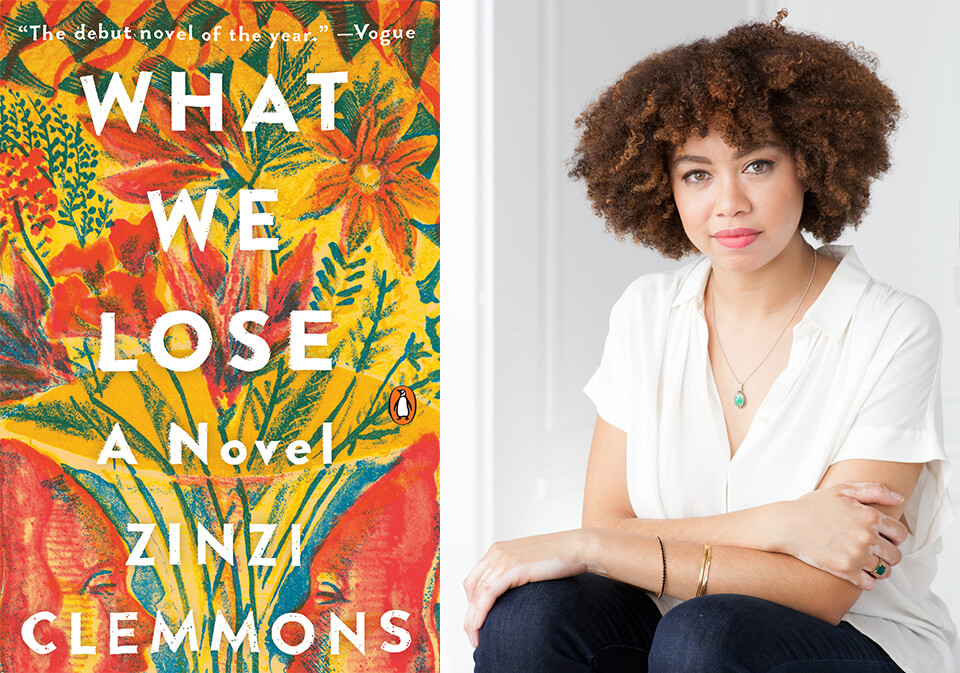

There are books you read, and then there are books that read you. What We Lose by Zinzi Clemmons falls firmly into the latter category.

It’s a tender, experimental, and quietly powerful novel that explores the deep complexities of grief, identity, and the uncomfortable space in between belonging and alienation. At its heart is Thandi, a young woman trying to find her place in a world that constantly tells her she doesn’t quite fit in.

Thandi is the daughter of a Black American father and a biracial South African mother. She grows up in a privileged, middle-class neighbourhood in Philadelphia, but her upbringing doesn’t shield her from the ever-lurking questions about identity.

She is light-skinned, well-educated, and globally exposed—but these markers don’t make her immune to being “othered.” If anything, they sharpen her sense of dislocation.

In South Africa, where her mother is from, Thandi is not seen as Black. Her relatives and neighbours in Johannesburg view her with quiet scepticism.

Her attempts to assert her Blackness are met with confusion. Her light skin becomes a silent betrayal—an unspoken disqualifier. “How can a girl who looks like this be Black?” they seem to ask with their eyes.

Back in the U.S., Thandi doesn’t find full acceptance either. Among her Black American peers, her middle-class upbringing makes her an outlier.

She doesn’t fit neatly into the dominant narratives of struggle, poverty, and resilience that shape Black identity in America.

Instead, she feels like an uncomfortable reminder of difference—too privileged to belong, too Black to be white, and too white to be fully embraced by Blackness.

A Deeper Exploration of What we Lose

However, What We Lose is more than just a meditation on racial identity. It is also a devastating exploration of grief—grief that arrives suddenly, then lingers like a shadow.

Thandi’s emotional world is defined by the slow, painful loss of her mother to breast cancer. Her mother is more than a parent—she is Thandi’s grounding force, her anchor in a world that already feels unstable.

Clemmons writes these moments of loss with raw honesty. Thandi doesn’t just mourn; she unravels. She watches the woman who taught her how to exist in the world slowly disappear, and she can do nothing to stop it.

There is something incredibly haunting about the helplessness of it all. Anyone who has lost a parent or a loved one will recognize the ache—the numbness, the anger, the unbearable silence that follows.

As Thandi grieves, she tries to piece together a life. She falls in love with Peter, a relationship that seems promising but becomes increasingly strained.

When she becomes pregnant, she begins to realise just how disconnected she feels—from Peter, from her father, from her own emotions. The only constant presence in her life is Aminah, her best friend and confidante.

Aminah represents a kind of emotional stability, a quiet companionship that anchors Thandi even in her darkest moments.

The arrival of her baby boy, Mahpee—whom she lovingly calls “M”—marks a turning point. With him, Thandi begins to reclaim something of herself.

Her grief doesn’t disappear, but it softens, reshaped by the demands and tenderness of motherhood. She begins to pour her love, once reserved entirely for her mother, into her son. It is in this act—this quiet, deliberate decision to move forward—that she begins to heal.

Conclusion

Zinzi Clemmons doesn’t offer easy answers in What We Lose. The novel is fragmented, interspersed with photos, quotes, philosophical musings, and vignettes.

The form mirrors Thandi’s emotional state: fractured, searching, nonlinear. But this is what makes the book so intimate and true.

It speaks to the way we actually experience pain—not in tidy chapters, but in jagged memories and brief flashes of clarity.

What We Lose is not just a story about race, or grief, or coming of age. It is a story about the tension of being—of living in the in-between, of carrying loss as both wound and inheritance. It’s a deeply personal, hauntingly beautiful exploration of what it means to love, to lose, and to try—imperfectly—to go on.

Trending

Trending