The latest SBM Jollof Index Q4 2024–Q1 2025 is not just a deep dive into the price of West Africa’s most beloved dish. It’s a clear indictment of the region’s mounting food insecurity, spiralling inflation, and economic fragility. A pot of jollof rice may be comforting, but what it now costs to cook one is anything but.

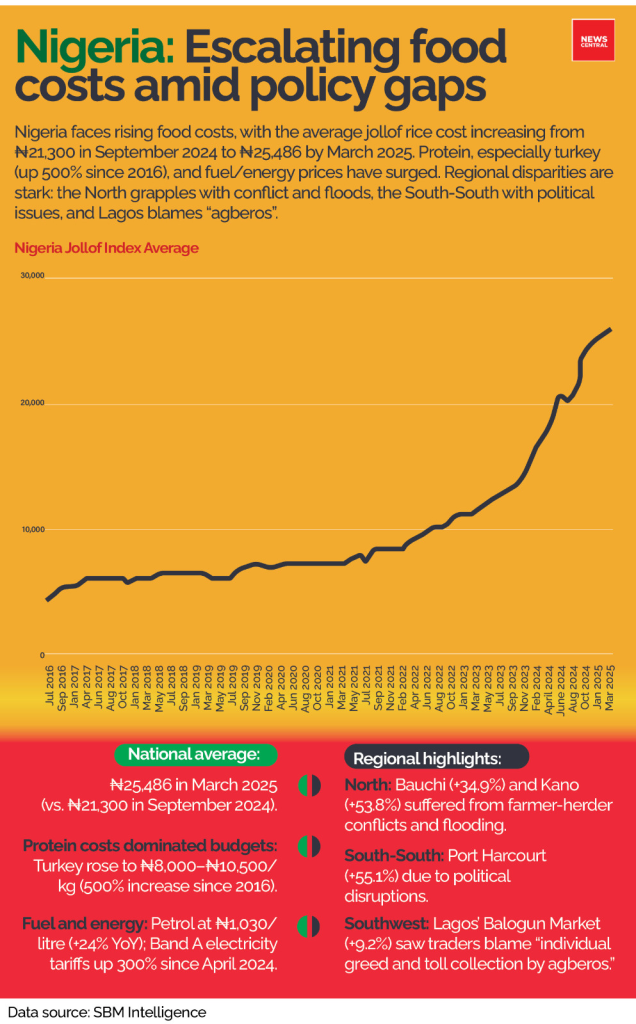

From Nigeria to Ghana, jollof is more than a meal. It’s a cultural staple, a proxy for economic health, and increasingly, a stress test for food affordability. Between September 2024 and March 2025, the average cost of preparing a pot of jollof for a family of five in Nigeria surged from ₦21,300 to ₦25,486—a staggering 19% increase. In some cities, the jumps were brutal: Port Harcourt (+55.1%), Kano (+53.8%), and Bauchi (+34.9%) all lead the hall of shame.

“Protein, in particular, remains a major contributor to the overall cost, with turkey now costing between ₦8,000 and ₦10,500 per kilo,” SBM reports, “a substantial increase from the ₦1,500 to ₦1,700 it cost in 2016.”

Who knew poultry inflation could ruffle these many feathers?

A confluence of factors has turned the humble plate of jollof into a luxury item. These include:

- Rising energy and fuel costs: Petrol hit ₦1,030/litre, while Band A electricity tariffs skyrocketed by 300% since April 2024.

- Insecurity: Farmer-herder clashes and banditry in Benue, Borno and Plateau States have displaced millions and wrecked agricultural productivity.

- Climate shocks: Erratic rainfall, floods and droughts led to cereal production deficits and food system strain.

- Logistical nightmares: From poor transport infrastructure to “agbero”-infested Lagos markets, every leg of the food supply chain adds cost.

In Lagos’ Balogun Market, traders reportedly blamed price hikes on “individual greed and toll collection by agberos.”

A Tale of Two Countries

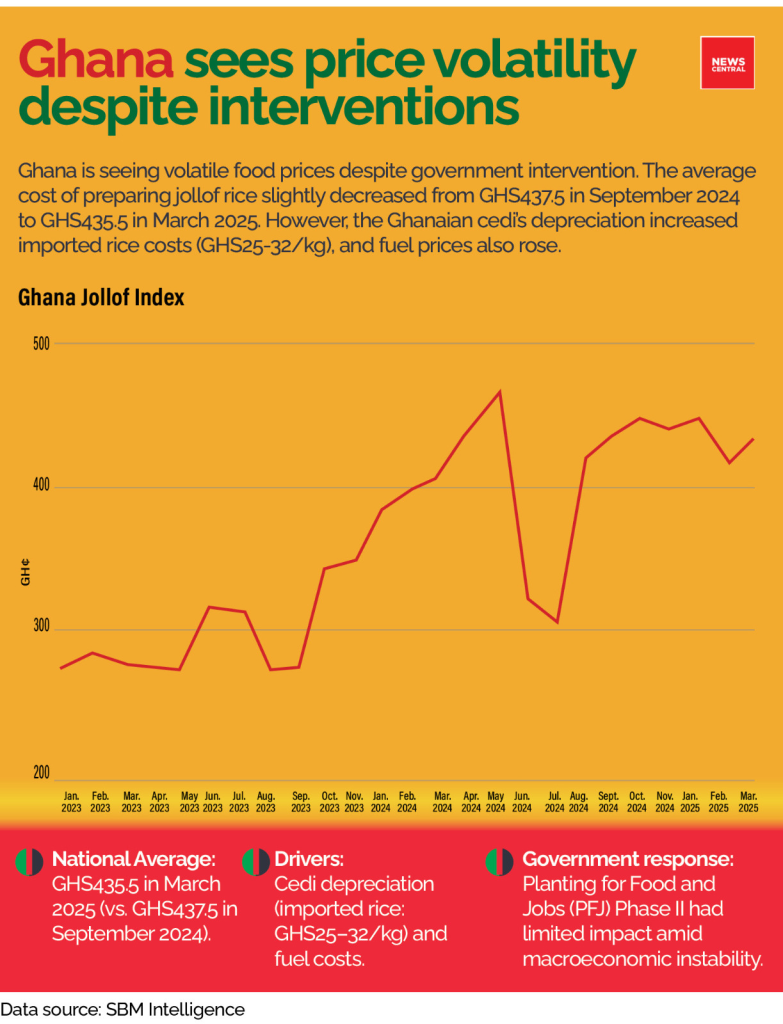

While Nigeria is boiling under price shocks, Ghana is simmering in its own stew of import dependency and currency depreciation. Though jollof rice prices in Ghana dipped slightly—from GHS437.5 in September to GHS435.5 in March—the average cost is still 78.7% higher than in Nigeria (using official rates), thanks largely to the weak cedi and rising import bills.

“Despite the ongoing efforts of the Ghanaian government… food price volatility remains a significant feature of the Ghanaian economy,” the report notes.

The planting-for-food agenda might be noble, but the ground realities remain unfavourable.

A Pot Boiling Over

This isn’t just about jollof. The price of this dish reflects deeper fractures: systemic poverty, fragile supply chains, and years of policy inertia. Urbanisation, population growth, and youth unemployment mean food access is increasingly tied to economic dignity. In the words of the report:

“Without structural reforms prioritising agricultural investment, conflict resolution, and regional collaboration… food prices are projected to remain elevated until 2025, exacerbating malnutrition and increasing the risk of social unrest.”

Short-term subsidies and token food interventions won’t cut it. Governments must urgently:

- Invest in mechanised farming and regional food reserves.

- Build resilient supply chains and fix rural infrastructure.

- Roll out tech-enabled market monitoring systems.

- Curb profiteering and ensure transparent food pricing.

And yes, let’s not forget digital literacy for food supply agents, because tracking inflation requires more than a pot of stew and a wooden spoon.

The Jollof Index doesn’t just chart food prices; it maps a crisis of governance. In a region where food riots aren’t far-fetched, and elections are often won or lost on the price of rice, policymakers can no longer afford to ignore what’s cooking in the average household’s kitchen.

“The time for piecemeal solutions is over… failure to act risks condemning an estimated 52.7 million people to acute hunger by mid-2025.” Nigeria and Ghana must take the heat before the pot burns.

Trending

Trending