A democracy rarely collapses in a single dramatic moment. More often, it is slowly redesigned—clause by clause—until citizens wake up one day to discover that elections still happen, but accountability no longer does.

Nigeria’s democracy is not being overthrown; it is being edited, not with tanks on the streets, but with clauses in a bill and sometimes the most dangerous edits are those presented as “technical clarifications,” because they preserve the very loopholes that have repeatedly eroded public trust.

On Wednesday, February 4, 2026, after concluding deliberations on proposed changes to the Electoral Act 2022, the Nigerian Senate passed the Electoral Act Amendment Bill. But the most consequential choice was not what it passed; it was what it refused: a proposal that would have made electronic transmission of polling-unit results to the public results portal compulsory in real time. Senate leaders insisted that INEC may still deploy technology and that the existing framework was being retained.

That defence is precisely the indictment. The Senate did not ban electronic transmission; it refused to guarantee it. In Nigeria’s electoral history, that distinction lies between deterrence and discretion. When transparency is optional, rigging becomes strategic. When evidence is discretionary, truth becomes negotiable.

The Electoral Act framework leaves the manner of transferring results to what INEC prescribes, and INEC’s explanatory note on the Act acknowledges that the process remains “basically still manual,” despite provisions for electronic transmission. In practice, this is how loopholes survive: the public is told that technology exists, but the law permits it to be applied inconsistently, delayed, or sidelined at the decisive hour.

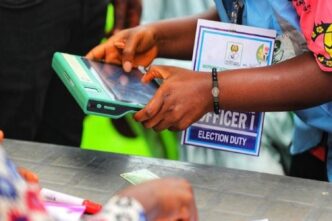

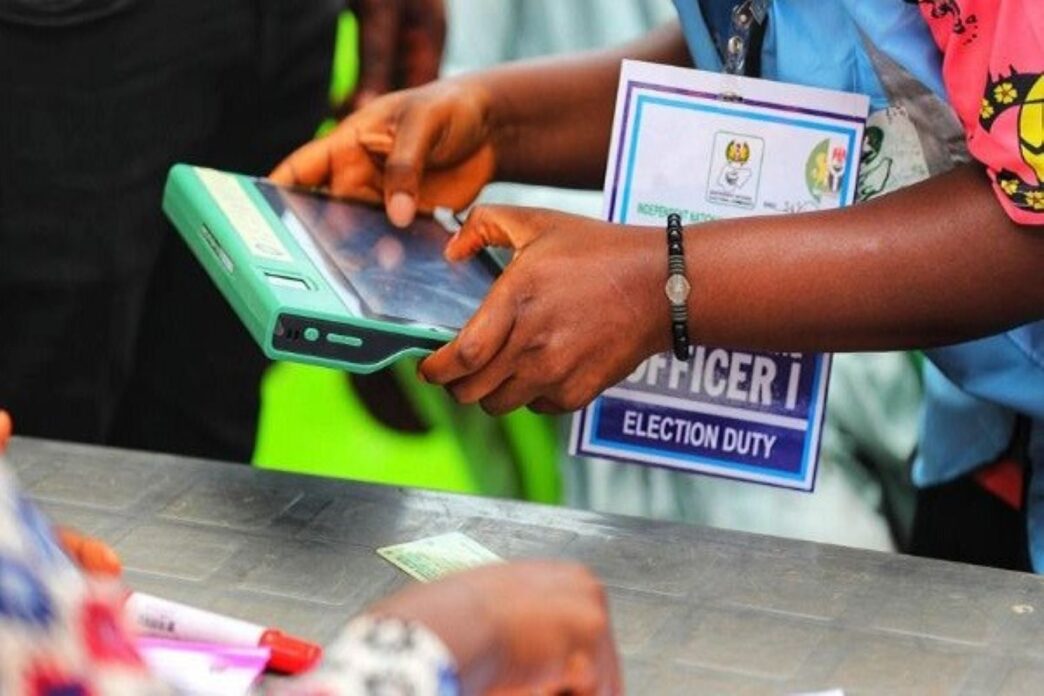

The point is not to fetishise gadgets. It is intended to protect the only part of the results chain that citizens can directly observe. At the polling unit, party agents, observers, voters, and cameras can witness the count converge into a result. Once the process migrates into the collation chain—often late, often under pressure, often with limited visibility—the opportunities for manipulation expand: delay, substitution, intimidation, arithmetic, disappearance of forms, or the deliberate creation of inconsistencies that later become the raw material of litigation. A mandatory, time-bound polling-unit upload does not create integrity by magic, but it reduces the distance between the voter’s will and the publicly verifiable record of that will. Refusing to lock that safeguard into law is therefore not a neutral act. It is an open endorsement of the conditions that make rigging feasible and deniable.

This is why many Nigerians interpret the Senate’s move as an exposition of a 2027 rigging plan. Not necessarily because a conspiracy has been formally scripted, but because the architecture of plausible deniability is being put in place in advance. If electronic transmission is merely permitted, then when the next high-stakes contest arrives, the beneficiaries of opacity will have ready-made alibis: “network issues,” “INEC didn’t prescribe it,” “manual collation remains lawful,” “the portal is for viewing,” “no clause was violated.” The election becomes a courtroom drama after the fact rather than a verifiable civic process in real time.

THISDAY captured the legal background many Nigerians recall from 2023: the Supreme Court held that electronic transmission was not mandatory under the 2022 law and that IReV is primarily a viewing portal, not the legal site of collation. Instead of legislating away this ambiguity, the Senate has effectively chosen to preserve it into 2027.

There is also a cruel irony in the package of reforms that the Senate retained. It kept BVAS for accreditation—confirming that voter accreditation will continue to rely on biometric verification and that manual accreditation remains illegal. It also maintained PVC as the sole valid form of voter identification at polling units. It reportedly adjusted penalties for certain offences, including PVC-related misconduct, by increasing fines in some cases. In other words, lawmakers are comfortable using technology and strict rules to police citizens at the entry point of the process, while refusing to impose strict, technology-enabled transparency at the exit point where political power is actually awarded.

Defenders of the Senate’s position try to narrow the debate to semantics and logistics: that the contention is “real time,” that network coverage is uneven, that the Senate did not reject electronic transmission but declined to mandate it in a specific manner. Senator Victor Umeh, for example, publicly suggested that support for electronic transmission was broad in earlier consultations and within Senate processes, and that disagreements later crystallised around the “real-time” framing. But the real issue is not vocabulary. It is trust. A serious legislature, confronted with connectivity constraints, would build redundancy into a mandate—store-and-forward syncing, time stamps, multiple transmission pathways, clear exception thresholds, audit trails, and sanctions for sabotage—rather than retreat into discretion. Nigeria is not technologically too poor to legislate transparency; it is politically too conflicted to do so without pressure.

And public trust is not an abstract commodity. Nigeria is still living with the aftertaste of 2023, when the credibility of election technology collided with widespread controversy over the uploading of results to the viewing portal—so contentious that INEC later issued formal explanations and post-mortems explaining why Nigerians could not view some results in real time. One does not need to romanticise technology to see the lesson: when the public cannot verify results promptly and consistently, suspicion becomes rational. It is exactly this lesson—earned at high national cost—that the Senate appears determined to ignore.

This is the core reason many Nigerians interpret the Senate’s move as a 2027 rigging plan. Not because the future has been secretly settled, but because the architecture of deniability is being preserved. If electronic transmission is merely permitted, then whenever the next high-stakes contest arrives, the beneficiaries of opacity will have ready-made alibis: “the network failed,” “INEC did not prescribe it,” “manual collation is still lawful,” “the portal was not required,” “no clause was violated.” The election becomes a courtroom drama after the fact rather than a verifiable process in real time.

Democracy cannot survive on technicalities. It survives on consent. And consent survives on credibility.

That is why this moment is bigger than parties and candidates. Today’s loophole will not belong permanently to any one political camp. Sooner or later, the same ambiguity will injure those who defend it today. Short-term tactical gains by “invested stakeholders” are not worth the long-term corrosion of legitimacy. When citizens conclude that votes do not count, participation drops, civic anger rises, and extra-democratic temptations grow. The state becomes harder to govern because authority becomes perpetually disputed. Institutions—courts, security agencies, even the civil service—get dragged deeper into political battles they were never designed to resolve.

The Senate also tightened the electoral calendar, reducing the period within which INEC must issue notice of election from 360 days to 180 days, and shortening certain submission windows for parties, according to Channels’ reporting. Shorter timelines may appear efficient on paper, but in Nigeria’s political reality, they often favour entrenched machinery—those who already control party structures, resources, and logistics—while narrowing the space for credible primaries, internal democracy, and the maturation of alternative candidacies. When you weaken transparency and compress preparation time, you do not merely risk administrative strain; you increase the advantage of those best positioned to exploit opacity.

None of this is irreversible yet. The bill is not a law. The Senate’s version must be harmonised with the House of Representatives’ version through a Conference Committee before it goes to the President for assent; until then, INEC continues under the existing Electoral Act 2022. Premium Times reported the move toward conference harmonisation, underscoring that this remains a live legislative battle rather than a sealed outcome. That window matters. It is where Nigerians must insist—without euphemism—that transparency cannot be a courtesy granted by institutions; it must be a right guaranteed to citizens.

The democratic bottom line is simple. If the final law keeps electronic transmission optional, Nigeria should interpret it as a deliberate choice to protect against manipulation. If the final law restores mandatory polling-unit uploads with robust redundancy provisions, then lawmakers will have shown they understand that credible elections are not a favour to the opposition; they are a foundation for national stability. Democracy is not only the right to vote. It is the right to have your vote count in a verifiable way. When the law refuses to guarantee that verification, it invites apathy, fuels cynicism, and makes political competition more combustible—because if ballots do not settle disputes, other forces will try.

What should be demanded is straightforward: Make polling-unit result upload mandatory, time-bound, and publicly verifiable; define exceptions tightly (not vaguely); build in redundancy for low-connectivity areas; and attach penalties that deter sabotage and non-compliance. Anything less is an invitation to “manage” outcomes.

The Senate may refer to its decision as a retention of existing provisions. Citizens should call it what it is: electoral transparency in reverse gear—a deliberate refusal to lock the door against manipulation. And in a country trying to rescue its democratic promise, leaving that door open is not neutrality. It is complicity.

Nigeria cannot afford another election whose legitimacy is negotiated after the fact. If 2027 is to be a democratic turning point, then the law must stop flirting with opacity—and start insisting, without ambiguity, that the people’s verdict is not a private document to be transported, edited, and announced, but a public truth to be transmitted, seen, and owned.

Trending

Trending