In the quiet moments that follow the passing of a leader, a nation is compelled to reflect not just on what was done, but on who the person truly was.

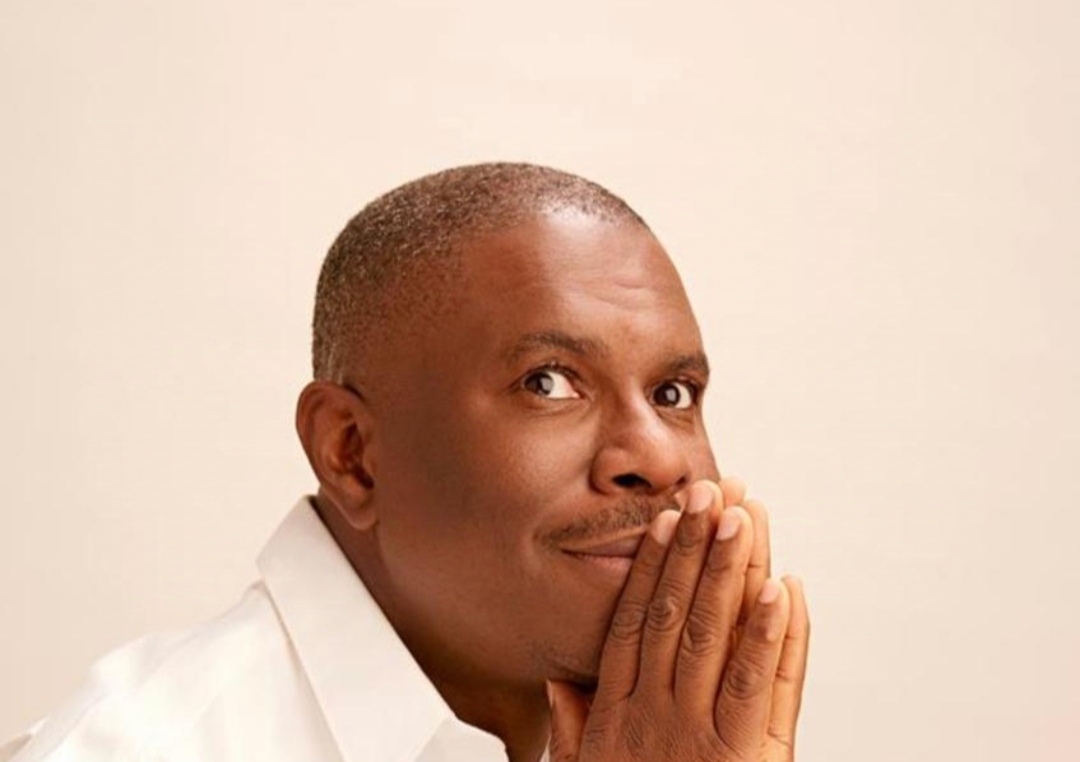

Muhammadu Buhari’s death has reopened that conversation in Nigeria, not in anger or celebration, but in contemplation. He was a man often described in simple terms: austere, disciplined, incorruptible. And yet, these same qualities, so admired in his private life, sit uncomfortably alongside the complicated legacy of his time in public office.

The gap between Buhari’s moral compass and the moral weight of statecraft is where the story becomes truly reflective. In that space lies the tension between character and consequences—between being good and doing good.

I find myself returning repeatedly to the image of Buhari as a lone sentinel of probity. In a nation where ostentation is sometimes mistaken for success, his frugal lifestyle felt almost subversive. He lived simply: a modest home, a small entourage, and a work schedule that eschewed pomp. He paid his electricity bills, avoided lavish ceremonies, and chose to live without the typical grandeur associated with power. For millions of Nigerians, that simplicity resonated like a quiet protest against decades of elite excess.

In a country exhausted by leaders who flaunted stolen wealth and treated public office as a reward for loyalty, Buhari was something else—someone who did not steal, did not hoard, and did not bow to the seduction of a corrupt system.

There was dignity in his restraint, and it became a powerful symbol of his character. To see a President or leader of his stature move through daily life without expectation of privilege was—paradoxically—both reassuring and unsettling. It reassured because it demonstrated that integrity need not be a rhetorical flourish; it unsettled because it forced us to ask why so few before him had displayed the same restraint. Ordinary citizens felt that even if he did nothing else, at least he would not rob them. That sentiment became his greatest political currency. It won him not just elections but deep emotional trust.

In many ways, Buhari did not have supporters—he had believers.

But personal virtue, as noble as it is, does not always translate into public good. Running a nation is inherently a collective endeavour: it demands robust institutions, vigilant watchdogs, and a willingness to enforce standards, even when it may bruise the powerful.

Here, Buhari’s presidency exhibited a curious dichotomy. On one hand, he spoke constantly of anti-corruption, lending moral authority to bodies like the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission. On the other hand, his administration sometimes seemed content to rest on symbolic gestures. This approach, rather than concrete actions, disappointed the public and eroded their trust. High-profile arrests gave way to charge-and-release cycles; institutional reforms were launched with fanfare but lacked sustained follow-through.

Buhari, the man of honour, often failed to hold others to the same standard. And in a society where corruption is rarely subtle and almost always systemic, his silence, abdication, or hesitation became complicity in the eyes of many. The same presidency that rose on the promise to end corruption saw some of the most brazen financial misconduct in recent memory.

In 2022, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) arraigned the Accountant-General of the Federation, Ahmed Idris, for embezzling over N109 billion. Despite Buhari’s anti-corruption rhetoric, the prosecution dragged, and no significant convictions followed during his tenure. The Auditor-General’s 2020 report revealed that over N300 billion in public funds were unaccounted for across MDAs, yet few consequences followed. Government under his watch borrowed recklessly, and by the time Buhari left office in May 2023, Nigeria’s public debt had ballooned to N77 trillion, up from N12.6 trillion in 2015—a six-fold increase. While Buhari himself was not personally implicated in theft, the system he presided over remained vulnerable and largely unrestrained.

The contradictions extended beyond money. His appointments, which tilted heavily toward the North, sent troubling signals in a diverse country already strained by ethnic suspicion. Of the 47 top security and intelligence appointments made during his first term, 35 came from the North, and 31 were Muslims. These figures raised concerns about inclusivity, national cohesion, and the perception of a government run through narrow identity lenses. The public’s perception of nepotism became difficult to ignore.

Farmers across the Middle Belt and South reeled from deadly herder attacks—over 7,400 people were killed in farmer-herder conflicts between 2015 and 2021, according to the International Crisis Group—while many felt Buhari’s government offered muted responses or lacked urgency. His critics pointed not just to what he did, but to what he failed to do. Why did he hesitate to sack underperforming officials? Why did he remain loyal to individuals facing credible allegations of abuse, mismanagement, or excess?

Buhari’s brand of leadership also shaped public expectations in ways both inspiring and challenging. When he vowed to defeat Boko Haram ‘within months,’ many believed him, buoyed by his military background and reputation for decisive action. However, when those promises fell short, the disappointment was palpable, cutting deeper precisely because the promise had been credible. Similarly, when sectors of the population saw apparent favouritism toward certain ethnic or regional groups, the sense of betrayal felt acute, especially given the trust he had cultivated through years of personal honesty.

These dynamics highlight a delicate balance: trust must be earned anew in each policy decision, rather than being merely inherited from personal reputation. A ruler who demonstrates personal restraint can shake the public’s cynicism—but only to the extent that their administration consistently enforces the same standards across all levels of power.

And yet, to judge Buhari solely by the weaknesses of his government is to miss the deeper question. What happens when a morally upright individual is placed at the helm of a morally broken system? Buhari tried to steer a bureaucracy bloated by patronage and haunted by inertia. He brought personal sincerity to a structure designed for self-interest. And while he spoke often of reform, few could point to enduring systemic overhauls. There were attempts to promote transparency—like the launch of the Open Treasury Portal in 2019, aimed at publishing real-time government expenditure—but even that portal was marred by ghost transactions and inflated figures, according to BudgIT’s 2020 report. He did not restructure the civil service. He did not radically modernise the judiciary. Procurement remained opaque, oversight agencies remained weak, and corruption adapted, evolved, and often flourished—sometimes right under his nose.

The force of personal example was powerful, but insufficient. A nation does not change because a single man is honest; it changes because systems force everyone else to be.

Still, people remembered. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the Director-General of the World Trade Organisation, spoke of his “undeniable discipline.” William Kumuyi, founder of the Deeper Life Church, praised his contentment and restraint. Aisha Buhari, his wife, described him as a man who lived and died for Nigeria. Even Olusegun Obasanjo, often his fiercest political critic, acknowledged Buhari’s honesty. “We disagreed on policy,” Obasanjo said, “but no one can deny Buhari’s honesty.” Perhaps the most telling tribute came from a roadside trader in Kano: “Even if he does nothing, he won’t steal.” That kind of trust is not easily earned. In a country where betrayal often seems baked into politics, Buhari’s restraint stood out—not as a tactic, but as a truth.

But moral leadership cannot stop at the self. There must be systems. There must be consequences. There must be reform that survives beyond one’s tenure. Buhari’s story, then, is not one of moral failure—it is one of moral incompleteness. He brought integrity to the presidency but lacked the boldness or ruthlessness to make others live by the same creed. He governed with clean hands but allowed too many others to stain the system. And the paradox of his legacy is that he leaves behind both admiration and disappointment. He showed that it is possible to lead without greed, but also that it is not enough.

As I reflect on Buhari’s journey, I am struck by a simple truth: moral integrity sets the horizon, but it does not chart the course. Leaders of conscience can illuminate the highest ideals—but without the ballast of strong institutions and the courage to apply principles impartially, good intentions will drift inexorably into compromise. For aspiring leaders, the lesson is twofold. First, cultivate a personal ethic that resists the seductive ease of privilege and self-interest.

Second—and perhaps more daunting—build systems that outlast any one individual’s lifespan: independent judiciaries, transparent procurement processes, and unflinching oversight bodies. Moral leadership is not solely a matter of character; it is also a question of architecture.

Nigeria has always longed for a leader it can believe in. Buhari, for many, was that figure. But belief must give way to expectation. The future must demand more. We must move beyond celebrating leaders for what they do not take and begin to judge them by what they give, build, and enforce. Buhari’s moral compass pointed north—but a compass alone cannot carry a nation. It must be matched with energy, with discipline, with institutional vision.

In the end, Buhari bequeathed to Nigeria a paradox that stirs both admiration and frustration. He proved that a head of state could live unencumbered by corruption. Yet he also showed us that the purity of personal example, on its own, cannot bend the vast forces of patronage, inertia, and political expediency. When we speak of “Mai Gaskiya,” the truthful one, let us remember the truth of his tenure: that personal integrity is a precious, but incomplete, remedy for the ailments of governance. The true challenge lies in transforming individual virtue into collective virtue—an enduring inheritance for the generations that follow.

In that endeavour, Buhari’s life offers both inspiration and caution, reminding us that moral leadership demands more than clean hands; it requires an unwavering dedication to shaping institutions that keep those hands honest. Buhari’s memory should remind us not only of what is possible in the moral character of a leader, but also of how urgent it is to embed that character into the state’s architecture. That, perhaps, is the work left unfinished. And that, perhaps, is the question the next generation must answer.

Trending

Trending