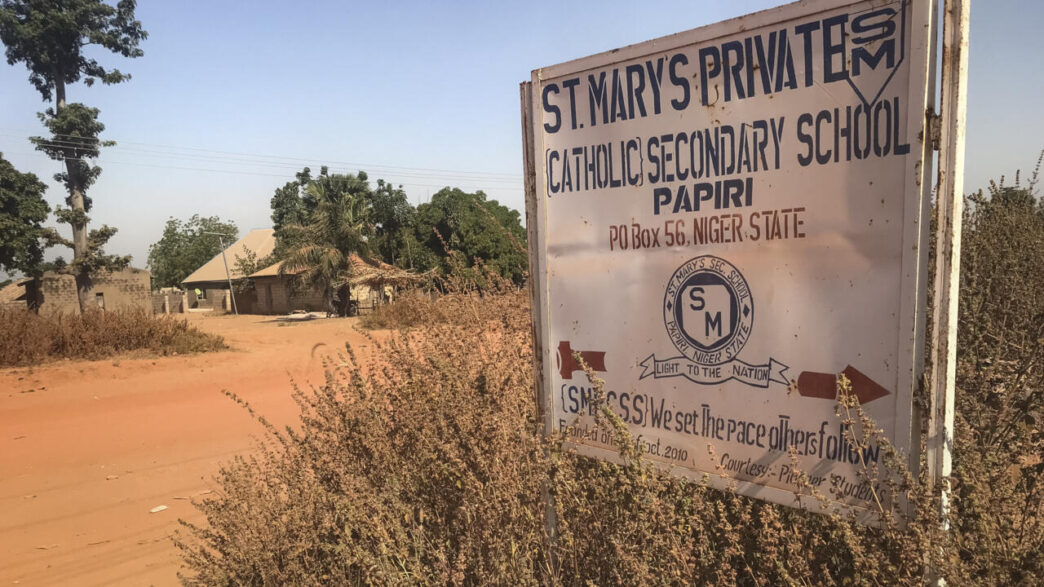

Nigerian authorities have confirmed the rescue of 100 abducted schoolchildren, weeks after gunmen stormed St. Mary’s co-educational boarding school in Niger State and seized hundreds of students and staff. A UN source and local media disclosed the development on Sunday, yet the fate of 165 others still believed to be in captivity remains disturbingly unresolved.

The mass abduction, which occurred in late November, involved 315 people. Roughly 50 fled soon after, leaving 265 hostages unaccounted for until this partial breakthrough. According to the UN source, the newly freed children have already arrived in Abuja and will be returned to Niger State authorities on Monday. “They are going to be handed over to Niger state government tomorrow,” the source told AFP.

Local outlets echoed the news of the 100 released, though none clarified whether the rescue was achieved through negotiation, military activity, or quiet back-channel arrangements. The circumstances surrounding the remaining captives are still unknown. Presidential spokesman Sunday Dare also confirmed the release to AFP.

At the Kontagora diocese, which oversees the school, there was cautious relief. Daniel Atori, speaking for Bishop Bulus Yohanna, said, “We have been praying and waiting for their return, if it is true then it is a cheering news.” Still, he stressed their lack of formal notice: “However, we are not officially aware and have not been duly notified by the federal government.”

Mounting Security Strain and International Pressure

Kidnapping for ransom has long plagued Nigeria, particularly in the north. But November’s spate of mass abductions — two dozen Muslim schoolgirls, 38 church worshippers, a bride and her bridal party, farmers, women, and children — peeled back the veneer on an already dire security landscape. Nigeria’s northeast is battling insurgency, while the northwest endures relentless assaults by heavily armed “bandit” gangs who raid villages and seize civilians for profit.

The perpetrators of the St. Mary’s attack remain unidentified. Yet the timing coincided with intense diplomatic posturing from the United States, where former President Donald Trump claimed that the killing of Christians in Nigeria amounted to “genocide” and warned of possible military intervention. Nigerian officials and independent analysts have rejected this framing, noting that such narratives — popular within segments of the Christian right in the US and Europe — oversimplify a nation of 230 million people experiencing overlapping conflicts that cut across religious lines. Farmer-herder clashes, separatist tensions, and jihadist violence have killed Christians and Muslims alike.

A Crisis Now Systemic

Nigeria’s mass kidnapping tragedy is not new. The 2014 Chibok abduction of nearly 300 schoolgirls by Boko Haram jolted global attention, yet a decade later the problem has evolved into what SBM Intelligence describes as a “structured, profit-seeking industry.” Their report estimates that between July 2024 and June 2025 alone, kidnappers generated roughly $1.66 million.

Analysts have debated whether Trump’s remarks emboldened armed groups. Some fear they may now see political value in holding civilians as shields, especially amid talk of possible US airstrikes. A Borno State official told AFP that militants could be preparing exactly for that scenario. Security observers have already detected US surveillance aircraft quietly circling jihadist forest enclaves in northern Nigeria.

For now, the release of 100 children offers a momentary sigh of relief — one tempered by the haunting question of what comes next for the many still missing.

Trending

Trending